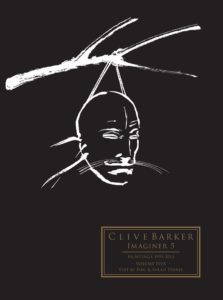

Imaginer 5 Review

Flesh and the Forbidden; A Marriage of Heaven and Hell

An Imaginer V Review

“I am a man, and men are animals who tell stories. This is a gift from God, who spoke our species into being, but left the end of our story untold. That mystery is troubling to us. How could it be otherwise? Without the final part, we think, how are we to make sense of all that went before: which is to say, our lives?

So we make stories of our own, in fevered and envious imitation of our Maker, hoping that we’ll tell, by chance, what God left untold. And finishing our tale, come to understand why we were born.” ― Clive Barker, Sacrament

(Author’s Note: having already done a previous review on Imaginer IV, which noted in depth the image-capturing process of the paintings, some of the history of the series itself, as well as more technical aspects of both the book and paintings, and fearing repetition (and with it, mundanity), I’ve decided to use this review more as an essay explicating the Volume’s central themes, as well as analyzing some of the paintings contained within, instead of as a mere review.)

Imaginer V Cover Image

The Imaginer series continues to swell and reach new exploratory heights in the fifth installment of the art-book series organized and designed by Clive Barker archivists, Phil and Sarah Stokes. As mentioned in my previous review of Imaginer IV, the Imaginer books are not only growing more ambitious in both scope and design with each installment, but more beautiful and theologically complex too, in terms of both its theme and text. In fact, I could not help but become gob-smacked by the sheer feeling of sublimity it was instilling within me as I flipped through the pages of this volume the first time. It was almost a theological tome to me: a book full of mysteries and miracles; divine deities and demons; as well as pieces on the flesh and the physical, as well as beyond the flesh, too—places and pieces of pure transcendence and transfiguration.

The feeling of its flipping pages reminded me of when I’d visited Clive’s Seraphim office for the first time. I’d remarked during the tour that, for me, personally, it was similar in feeling to that of a devout Catholic visiting the Vatican; one cannot help but feel insignificant and small in comparison to the vast and looming, endless images around. I was overwhelmed and inspired, elevated and elated, all at once, by the sheer creative output and imagination contained within its walls. And it is this exact feeling that I felt whilst going through this volume. There was a religiosity to it that only became more apparent as I progressed on through the book, delving more thoroughly into its text and images. In fact, it was only when I got to the text, in particular, in which this feeling of religiosity was brought wholly to the fore, exposed and expressed wonderfully in the Stokes’s magnificent introduction.

Sanborn in Adolescence

The Text

The introduction opens in the year 1995, chronicling the opening of the then newest Clive Barker art exhibition, ‘The Imagination of Clive Barker,’ of which “showcased pieces that addressed magic, alchemy, physical transformation and sexual preoccupations, (Stokes, 841.) Indeed, it’s the latter two of these of which seem to be the thesis of Imaginer V as a whole—the explication and exploration of both physical transformation and sexual introspection. The overall synthesis of the book is about the combining of the physical with the metaphysical; the sensual with the spiritual; the primal with the divine. It is an examination of all aspects of the flesh, as well as the forbidden—and the marriage of the two.

And the forbidden is not simply about our inner-most hidden desire, but that of our imagination as a whole; of our desire to seek and acquire knowledge that was forbidden to us by our makers, and through the use of our imagination, create our own personal mythologies to help us better understand ourselves, as well as the world around us. Indeed, the opening quote of the volume reads, “Imagination is a life-line that runs through our culture connecting the dream lives of today with the dream lives of those who went before us. It connects us to a source of knowledge and, potentially, wisdom,” (Barker, 833.)

The Patriarch

What Barker and the Stokes’s are trying to tell us, the readers, is that Imagination is the spring from which all mythologies flow, and what Barker in particular is trying to do, through his art—being the mythopoeist that he is—is answer all of our human quandaries of creation and theology through the construction of his own personal mythology. This personal mythology, of course, is presented to us here through an amalgamation of his paintings, writings, musings and poetry. For it is human imagination, as a whole, that is the road to our enlightenment, and thus, divination. That is how we, as a species and storytellers, access our inner-most imaginative state: by way through the forbidden and the sexual, the metaphysical and physical, to reach ultimate transcendence. And, truthfully, this is the conclusive causatum for any reader of Imaginer V—as you read and experience the personal philosophes of Barker’s, through the wonderful compilation of the Stokes’s opening essay, along with the betrothing of Barker’s endlessly imaginative paintings, you journey through his many worlds, mingling with his many characters and creatures, until you are wholly apotheosized by sheer imagination.

In philosophy, ultimate truth is called aletheia, and if I could sum up the Imaginer series with any one word, it would be just that: aletheia. How Mr. Barker has attained this ultimate amalgamation of aletheia here, in this volume, is by way of the forbidden and the flesh. “As a species,” Barker remarks, “we make a division between the things we can speak of in the presence of others and the things we can’t, that we are afraid of speaking about, perhaps because they go so deep into us, because they are so intimate. And I think that my job as a storyteller is to go to those places about which other people don’t particularly want to talk, and talk out loud. It fascinates me… The forbidden has been, since my earliest beginnings, my preoccupation,” (Barker, 842.) He further notes, on the point of flesh, in his artist’s statement of his One Flesh exhibition, “Flesh is our indisputable commonality. Whatever our race, our religion, our politics we are faced every morning with the fact of our bodies. Their frailties, their demands, their desires,” (Barker, 843.) He goes on in the statement to say that the point of his paintings in the exhibition is to shatter the molds of the taboo, and to excite the body and the mind; to enlighten and uplift both our physical flesh (in arousal) and our minds (in transcendence), to pure and utter transfiguration.

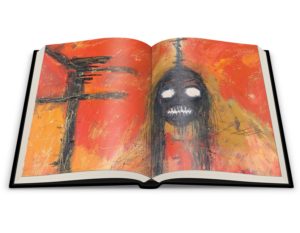

There is Light in Him Still, Detail Pages

And, by flipping through the pages of Imaginer V, one cannot help but feel that the volume accomplishes just this to its reader/voyeur. There is an utter religiosity to it that brings an absolute sublimity to its viewer, transmigrating the mind into higher states of the collective imagination. How it achieves this is not just through its exploration of the flesh and the forbidden, but too, through its marriage of heaven and hell, by way of its religious underpinnings. As a certain Barker-created Hell-Priest once remarked, the creatures held within this volume can indeed be “angels to some, demons to others,” depending on the bent of the onlooker, and thus, with it, to paraphrase Milton before him, it’s up to our minds to make heavens out of its hells, or hells out of its heavens.

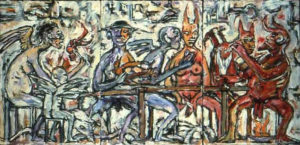

Angels and Demons Dining Together

In fact, it’s a pastel triptych featured in the volume’s introduction, in particular, that I believe encapsulates this idea perfectly: Angels and Demons Dining Together. Here, we are treated to the macabre and the innocent—an aroused angel being pleasured clandestinely by a demon; an apathetic child and its pet surrounded by feasting divinities indulging their carnal desires; genitals roasting in flame while fairies are pinioned of their wings. It is this unlikely marriage of the imagination that permeates all the works within, transcending their meanings into metaphysical marvel.

The Unconsumed

The entirety of the introduction is beautifully presented, with illustrations, in a 15+ page sweep of philosophical musings and historical insight—journeying from Mr. Barker’s 1995 opening exhibition, all the way through to 1998, with the inception of Abarat—and I truthfully dare not spoil any more of it here. Thus, to close this section, I will leave you with but one final quote from Mr. Barker: “I think our imaginations are a continuum. I think the divisions are artificial… I think that what we do in our culture is we say, ‘OK, here’s a time we have to be serious, now here’s a time we can be childish, here’s a time we can be sexy and here’s a time we can’t be sexy.’ I don’t think that’s how our minds work. I think actually sometimes, perversely, we can actually have things arise in our heads which are wholly inappropriate. You know, you’re sitting in church and a sexy thought comes into your head – what’s that doing there? Well, it’s because your subconscious wants it to be there and you have no control over it… I don’t think you should have control over it – I think we control our imaginations way too much,” (Barker, 854-855.) And indeed, as the paintings of this volume show, Mr. Barker’s imagination surpasses all boundaries.

The Paintings

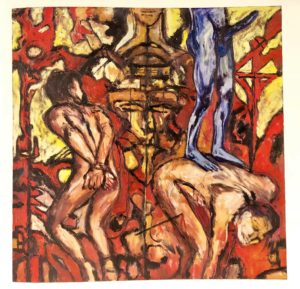

The Innocent and The Guilty

The wondrous beauty of the Imaginer books is the sheer amount of attention and thought put into them by their creators, Phil and Sarah Stokes. The selections of each volumes paintings are not random, but wholly purposeful. Each book contains within it, its own theme and overarching conceit, flowing from its text all the way to the paintings it represents within. Again, with nearly each canvas presented, we are reminded of Barker’s words on the forbidden and the flesh—and their unlikely marriage of heavens and hells. Flesh, as we see, is transformed and transfigured; worlds are built by demiurge craftsmen (and destroyed by annihilating chaos), and the erotic is merged with the innocent—all leading to the converging sublime religiosity of the imagination.

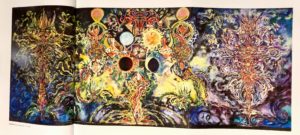

Untitled

One of the most glorious pieces featured within, an Untitled triptych of which is featured superbly across the newly utilized 30″ wide gatefolds, features at its center a figure engulfed entirely in flames, the licking fire lifting and infusing into all of the canvas surrounding it; the tendrils sweeping and spiraling into metaphysical abstractions; glyphs of imagination made physical across its mystical length. The piece is a Freudian wonderland, complete with womb-like worlds encompassed in spherical sex, along with Blakian suns and satellites blazing and spinning above its central character. All the while, betrothed on the left and right sides of the piece, are pure abstractions of gossamer god-like divinities. It’s a metaphysical masterpiece.

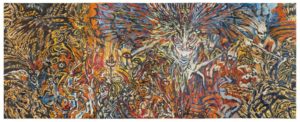

Thus

Another painting, titled The Innocent and The Guilty, feature two men tied in bondage, while an erect and headless demon-like character towers above, its hellish member pointed towards the heavens. In the center of the painting, the physical outlines of a metaphysical totem-like face. The piece is the epitome of the marriage of the flesh and the forbidden, intermixed with the metaphors of the bondage of religious ideologies, and the freedom from this by way of one’s own imagination. Another tryptic gatefold, titled Thus, features an ultimate holy war of the imagination, waged by divinities both good and evil on each side, with a central figure-head featured at its center. It is the appearance of these dualities within the piece that causes the soul to swell and transcend whilst viewing it.

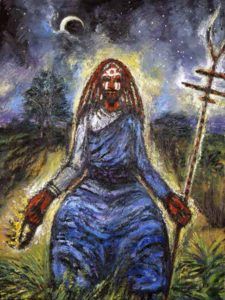

Brother Plato, Right or Wrong

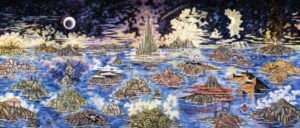

There are Abaratian pieces, both previously seen and never-before published, as well as characters such as The Unconsumed from The Scarlet Gospels, Galilee, and Nightbreedian creatures such as The Savior. Too, there are pieces obviously created for Barker’s own poetry, such as Brother Plato, Right or Wrong (of which brings me to a side-note—I think a wonderful future possibility for Barker’s work would be to have a book comprised entirely of Clive’s poetry, featuring the pieces’ betrothed paintings alongside the poesy. Alas, this fan can dream!) There are missions and monasteries; cities of lights and cities of garbage; deserts of spiraling absence and forests of fauvist color; the explicitly erotic among Seussian, childish creatures; there are the islands of the Abarat (The Beautiful Moment, featured not only in a glorious gatefold, but followed by two wondrous detail pages); and too, there are pieces featuring both crucifixions and resurrections.

The Islands of the Abarat (The Beautiful Moment)

Genesis

Revelation

However, the two pieces I found most stunning of all were two circular canvases titled Genesis and Revelation, respectively. On one, as we spiral out from its center, we are shown the vision of life’s creation. From a minuscule dot is birthed life, spiraling from lizards to birds, from birds to mammals, from mammals to the abundance of fish in all the seas. It is literally the cycle of life, and all Abaratian evolution displayed before us. On the other hand, in Revelation, we cycle from circles of fire into almost stained glass religious reliefs, spiraling all the way into the spiritual abstractions of pure Platonic transcendence. In Genesis, we see life, from nothing, be birthed into everything—all of existence—by pure imagination alone, into literal flesh and bone; and in Revelation, we are brought forth from the fires of the inferno—of the forbidden—and into the abstraction of pure and utter and whole imagination. It is here, with these betrothed pieces, in which we see all of Mr. Barker’s ideas—of which the Stokes have laid out consummately before us—converge into a perfect singularity.

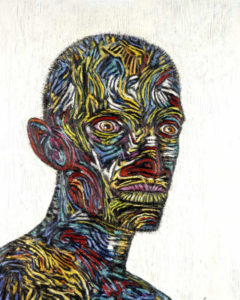

The Many Faces of Christopher Carrion

Finally, one of the last paintings shown in the volume is a piece titled The Many Faces of Christopher Carrion. In it, we see three panels of contorted faces connected by feathery tendrils of chaotic color. We see anger and anxiety and happiness and melancholy; we see all of the paradoxes of the flesh, and of life, and with it, all of the facets of life itself, held within it—a beautiful and perfect way to end an absolutely extraordinary book.

Final Thoughts

In the Desert

In closing, if I may, I’d like to finish with a personal story: two days after Imaginer V arrived in my possession, I was in Dallas, Texas, at Texas Frightmare Weekend waiting to meet Mr. Barker. It had been over a seven hour wait to see him, and the entire time I clutched the volume close to me, eager with anxiety and anticipation to meet the maestro himself and have him sign my copy. And here, as I waited in line with so many fellow fans of Clive’s—many of whom had, like me, traveled across the country just to meet him—I realized one thing: that many of them had not a clue he painted.

Orange and Black Trees

One woman in particular, who worked the line, allowing how many could go into the room to see Clive at a time, asked me while we waited for a previous group to finish, what I was clutching in my hand. I told her it was a book of Clive’s paintings. “He paints?” she asked, obviously surprised; her voice a mixture of curiosity and enthusiasm. A glint of mischief then entered my eye, and I quickly opened one of its pages to the first gatefold I could find. As I sprawled the pages open, revealing the fauvist world held within, her eyes immediately widened as her jaw slackened. “Clive painted that?!” she exclaimed. I then let her flip through the proceeding pages. As I watched her, I could not help but note the child-like wonder that crossed her face. And yet, too, there was the sight of absolute sublimity shimmering in her eyes. It was the awe of discovering something truly extraordinary; the transcendence of discovering something that can only be described as holy, as sacred, and important.

Hark’s Harbor

That is how these books make me feel. They’re not just mere books of paintings, but hold within them the deepest philosophies of one of the greatest imaginers of our time—of ANY time, to be exact. Clive Barker truly is the ultimate myth-maker—a storyteller tapping into shamanistic aspects of mythology to build his own—and with that, the ultimate Blakian demiurge-craftsman of invented worlds. And this fact could not be any more evident than through this amalgamation of his prose, poesy, paintings and philosophy contained within this book. If you’re a fan of Barker’s, I beg you, get these books, for if there ever was one series of books that could open your mind and elevate your spirit into a true, limitless world of mythology, philosophy, and imagination, it is indeed the Imaginer series.

You can purchase Imaginer Volume V here.

The Saviour

Imaginer V Volumes

Galilee

(Photos courtesy of The Clive Barker Archive and Clive Barker: Revelations)