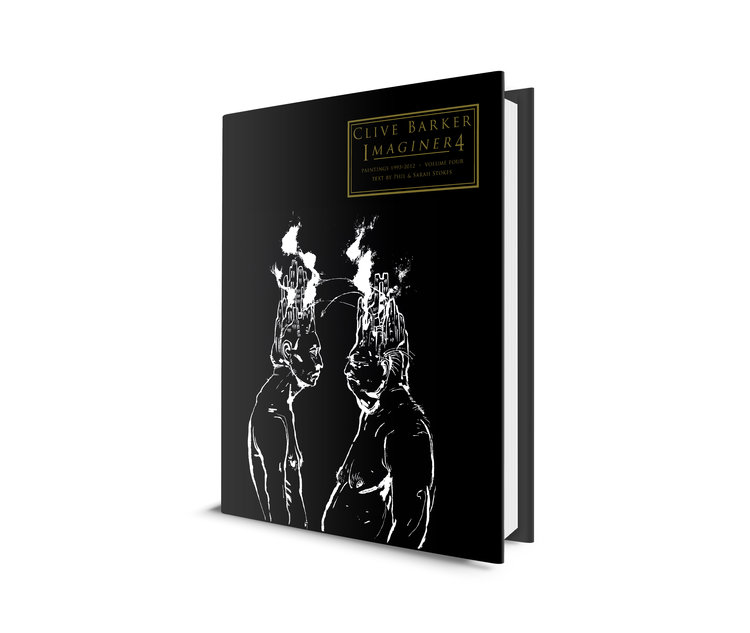

Imaginer 4 Review

“I want to be known as an imaginer.” -Clive Barker

“I want to be known as an imaginer.” -Clive Barker

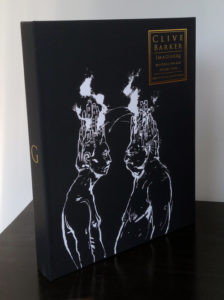

When asked during an interview with Stanley Wiater what a business card with his name on it would say in regards to occupation, Clive Barker answered with but one word: “Imaginer.” And, it seems, this is the premier description one can give Barker; he’s an author, filmmaker, poet, playwright, photographer, painter—there is no one single word to describe him other than indeed Imaginer. Thus, it’s from hence the title for his series of art books comes, Imaginer, which feature Clive Barker’s large-scale oil paintings from 1993 to 2012.

First devised as an eight-book series by Thomas Negovan—who wrote and assembled the first two in the series, crowd-funding them on Kickstarter—the Imaginer series has since been taken over by Clive Barker archivists and scholars, Phil and Sarah Stokes, who have recently released the newest volume of the series, Imaginer 4. And trust me when I say it couldn’t be in better or more capable hands. Besides Barker himself, no one knows his words, worlds and mind itself, better than Phil and Sarah Stokes. As Clive once said of them, they are ‘the keepers of his thoughts and meanings’, and Imaginer 4 is the perfect example of this truth. It is a glimpse behind the curtain; a transcendence of the physical boundaries of the flesh, and a transmigration straight into the metaphysical mind of the artist who Publisher’s Weekly once deemed as “one of modern fiction’s premier metaphysicians.” I truly feel there is no closer or more intimate way into the mind of Clive Barker than through reading and experiencing the Imaginer series.

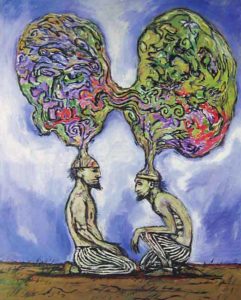

Sure, reading a novel by Barker is an intimate and engaging experience, but it is a mutual exchange and conversation between the reader and the author, not a wholly singular image. The author gives the words and weaves the tale, but the reader designs it; builds it; directs it. Like a painting of Barker’s titled ‘Two Shamans Sharing Thoughts’, the images derived and conjured from a novel are an intimate consummation between the two parties, for no two people will see the same images and experience the same things on any one written page. Whereas with Clive’s paintings, it is a singular vision—his vision, wholly. Every brush stroke, every glob of paint, every scratch of the palate knife (or sometimes even steak knife) is his own. They are an exclusive vision that is transcribed from his mind’s eye and recorded down on canvas via paint and brush. To flip through the pages of the book is to peel through the layers of the creator’s mind and soul. I honestly feel that the paintings of Clive Barker are the rawest, purest and most singularly synthesized form of intimate creation he makes. There is no film producer or publishing editor dictating certain things about the piece—they are pure Barker through and through. And accompanying these images is the remarkable and impeccable insight of Phil and Sarah Stokes.

The Text

The book opens with a quote from Clive Barker, of which I feel summarizes this book, the series, and the art of Clive Barker as a whole: “Imagination is our way of communication with what is profoundest in us.” Phil and Sarah Stokes, from the get-go, want us—the audience—to know that the most meaningful and powerful thing mankind has created as a species is indeed art. Too, that the most profound, intimate and purest of art-forms Barker creates in are with his paintings.

The text then proceeds to an introduction by Phil and Sarah Stokes titled, “Making A Mess.” It opens at the dawning of 1993, and chronicles Clive’s first true foray into the art world with the opening of his first-ever gallery exhibition—Light, Wisdom and Sound—and public reveal of his newest artistic endeavor: large scale oil canvases.

Throughout the introduction, both the Stokes’ and Barker, remark upon the power of imagination and that the conduit to wield said power is, for Barker, with that of a paintbrush. The Stokes and Barker argue that his paintings are journalistic, “a direct representation of what he holds in his mind’s eye,” and that they aren’t merely for stories or ideas, but are literal dream-images he sees in his mind’s eye laid bare on canvas. Yes, some of the images may give a spark of inspiration for a future tale, but at the time of the painting, there is no other objective than to simply chronicle and conjure the dream-image into reality.

And it is this chronicling of raw dream-images from his mind, directly to the canvas, as to why the paintings contained within the volume are so powerful. Barker remarks that he doesn’t make the paintings any more epic or different than they are in his head, for they don’t need to be. They are the direct images from his mind, born into the physical world, and that is enough—that is what gives them their power; their credence; their truth. The Stokes say, for Barker, the act of oil painting is “an evocation of the spiritual and sacred,” and Barker himself states that painting is almost an antithesis to his writing; his writing is structured and rhythmic, whereas painting is messy and raw.

Barker later states that he hopes—through his paintings—to make art accessible to all, and to demolish the notion that art is only for the elite. “Art has to be democratic,” he says. “I loathe elitist art.” As well, he notes that art and the act of imagining are sacred, and need to remain so. These are the philosophies he holds whilst painting, and flipping through the pages of Imaginer 4, that couldn’t be more evident.

The Stokes do an astonishing job weaving together quotes from Barker, along with analytical interpretation, critique and insight of their own, making this a seminal piece on the philosophy of not just Clive Barker’s art, but on both art and Clive Barker as a whole. It touches upon primal images, symbolic images, the act of creation, and the use of the fantastical and abstract worlds to reflect on our own reality and the physical world. It remarks on how Barker’s work consists of many “portraits” of beasts, monsters and creatures of whom stare out from the canvas, at us, the audience, making us reflect upon our own selves and our own inner-being. These paintings are not just reflections of the images Barker sees in his mind, but too are reflections of our own inner selves: the primal, the sacred, and the imagined. As well, they are reminders that the most powerful tool a human-being can wield is that of art, and that the most sacred of occupations one can have is that of creator; artist; imaginer.

The introduction contains many more wonderful quotes, passages, meditations and philosophies by Barker and the Stokes’ on art, but I dare not spoil much else here; it’s best to read and experience it for one’s self. However, as a final note, I will say that Phil and Sarah Stokes and Clive Barker remind us that our truest selves are held within our minds—in our imaginations—and that the best way one can show the world the essence of our truest inner-beings is through the creation of our own art.

The Paintings

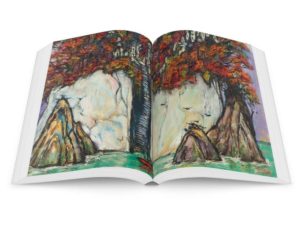

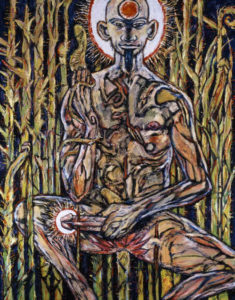

Held within the volume are 68 full-color facsimiles of some of Barker’s large-scale oil-paintings, as well as 22 close-up detail shots of some of the featured paintings. Anyone whose seen Barker’s work in person, or is familiar with his style, knows that a Clive Barker painting has its own geography and topography; its texture is chaotic and rugged, like chromatic mountains, and the density of the oil thick. (I was once told that a painting Barker had once done of the hell-priest himself, Pinhead, had to have weighed approximately thirty pounds in oil-paint alone.) Barker is known to do layer-upon-layer of paint, usually scrapping the top layers off with a knife to reveal the hidden colors beneath. And it is this technique that makes the close-up shots featured within the book so astounding. You’ll find yourself getting lost for long intervals at the complexity of the swirling colors and lines and details featured in the close-ups. It truly is as close as one can get to viewing the paintings in person. The paintings were all captured using a high-resolution camera, then painstakingly color-corrected to match the painting perfectly, so you can guarantee it’s like they’re right before you, hanging in a virtual gallery. I was also once told that you could project any of the paintings on the side of a several-story building and the images wouldn’t lose a pixel of detail, thus the detail-shots presented within are truly glorious; from the weave of the canvas, to the shape of the individual globs of paint, to the knife-scrapes, to even the tiniest of brush-strokes can all be discerned on any given page of the detail shots. Again, you’ll find yourself getting lost at long intervals whilst flipping through the pages.

I was also once told that you could project any of the paintings on the side of a several-story building and the images wouldn’t lose a pixel of detail, thus the detail-shots presented within are truly glorious; from the weave of the canvas, to the shape of the individual globs of paint, to the knife-scrapes, to even the tiniest of brush-strokes can all be discerned on any given page of the detail shots. Again, you’ll find yourself getting lost at long intervals whilst flipping through the pages.

Another notable thing is the arrangement in which the paintings are presented. The Stokes put tremendous time and thought into which paintings should go where, and which paintings should precede and follow which. As much as I love the first two Imaginer volumes, this attention to detail is only something I’ve truly noticed and admired in the volumes the Stokes’ themselves have compiled. Their vast knowledge on the art of Barker seemingly has allowed them to know exactly what paintings complement one another best, and which to feature where.

The choice paintings featured in this volume are exceedingly unique and intriguing. There is an abstract, almost metaphysical essence permeating this volume that is far more present here than in the preceding volumes. Many of the paintings are of loosely constructed geometrical landscapes and shapes that seemingly defy the laws of physics, transforming themselves into whatever impossible abstraction they desire. But this abstraction isn’t only limited to landscapes, for it oozes too into several of the creatures featured within as well, creating an even deeper mythological and metaphysical breadth to the images. Some of the paintings feature figures displayed along primal looking symbology and imagery, adding an even more tribal and shaman-like nuance to them. And this tribal and abstract essence also touches into the erotic pieces featured in the book as well—showcasing and intermingling the nude human frame with the textual aesthetic of primal symbols.

One final note is that a lot of the paintings featured in this volume seem extremely rare, if ever publicly exhibited. As one who has on many occasions perused and perused again the Stokes’ archive of Barker’s art, I’d honestly thought I’d seen it all—until I opened this volume, that is. Many of these paintings seemed new to me, and that made it all the more exciting to flip through the pages. If these paintings have ever been shown publicly prior to this release, it’s had to have been few and far between, for I can honestly say I think many of the paintings featured will be new to most viewers. I firmly believe even the most ardent Barker fan will find at least a couple paintings in this volume that they’ve never seen before. And that alone, I believe, is worth the price of admission.

Final Verdict

Imaginer 4 is not only arguably the best volume in the series thus far, it is honestly one of the best books on Clive Barker to have been released. Ever. Through its intermingling of words and images, I can’t imagine even the most ardent, stringent or passive of audience members coming away from this book unmoved and unchanged. It is a meditation on the power of art, the personal philosophy of Clive Barker, and a reminder of how sacred and important the imagination is. As well, it is the prime example of why Clive Barker is one of the most extraordinary and preliminary imaginers of our time. One cannot flip through its pages without having to pick up their jaws at least a handful of times at the sheer enormity and boundlessness of his imagination. If you’re just a casual fan, or an ardent one, it doesn’t matter—this book is a must. Do yourself a favor, and experience it for yourself. Get this book now.

(Photos courtesy of The Clive Barker Archive and Clive Barker: Revelations)